Contents

- Baby F (twin)

- NEW: Dr Shoo Lee's Panel Conclusions

- Prosecution opening statement

- Defence opening statement

- Defence Closing Speech

- Agreed Facts

- Recorded Events and Messages

- Later Facebook searches and Messages

- Demo of Alaris Pump (for infusions)

- NEW: Lucy Letby in the Witness Box

- Direct Examination

- Cross-Examination

- Witness Evidence

- Dr Gail Beech

- Nurse Shelley Tomlins

- Nurse Sophie Ellis

- Nurse Belinda Williamson

- Doctor C (Thirlwall: Doctor ZA)

- Dr John Gibbs

- Nurse - unnamed

- Dr Anna Milan

- Dr David Harkness

- Nurse A (Thirlwall: Nurse T)

- Ian Allen - Pharmacy

- Expert witness evidence

- Professor Peter Hindmarsh

- (Table of blood sugar readings)

- Professor Sally Kinsey

- Dr Sandie Bohin

- Dr Dewi Evans

- NEW: Police Interview Summary

- NEW: Thirlwall Inquiry Evidence

Main Page

Baby F (twin)

Count 6: Attempted murder of Baby F on 5 August 2015 (Insulin Poisoning)Dr Shoo Lee's International Panel Summary Conclusions

BABY 6 SUMMARY [Baby F]

Baby 6 was a 29+5/7 week, 1.434 kg birth weight, twin 2, borderline intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), male infant who was born by emergency Caesarean section for absent end diastolic flow. He had mild respiratory distress syndrome and hyperglycemia requiring insulin treatment. On 5/8/15 at 0130 hours, he developed sepsis and hypoglycemia, and was treated with antibiotics and intravenous (IV) glucose infusion. Over the next 17 hours, his blood glucose remained low (range 0.8 to 2.4) despite repeat boluses of 10% dextrose. At 1000 hours, his long IV line was noticed to have tissued; with extensive swelling and induration of the right groin, thigh and leg. IV fluids were stopped from 1000 to 1200 hours while a new long line was inserted. At 1200 hours, the IV bag was changed. At 1900 hours, the dextrose infusion was increased to 15% and the hypoglycemia resolved.

CONVICTION

It was alleged that Baby 6 was given exogenous insulin through the infusion bag because there was a prolonged period of hypoglycemia, his blood glucose inexplicably rose from 1.3 to 2.4 when his dextrose infusion stopped from 1000 to 1200 hours, his blood sugar rose after his infusion bag was changed at 1900 hours, and he had high insulin but low c-peptide levels which indicates exogenous insulin was used.

PANEL OPINION

The hypoglycemia started with sepsis and was prolonged because the IV infiltrated for several hours. When hypoglycaemia persisted despite 10% dextrose infusion, a higher glucose infusion should have been given earlier. Repeat boluses of 10% dextrose worsen hypoglycemia because they cause surges of blood sugar, which trigger surges of insulin secretion, resulting in a yo-yo pattern of sharp rises and falls in insulin and blood sugar. When the dextrose infusion was stopped from 1000 to 1200 hours, the blood sugar did not rise from 1.3 to 2.4 as alleged, because the blood sugar was 1.4 at 1146 hours. The 2.4 level was measured after 1200 hours, when the IV was restarted. Since infusion bags were prepared in the pharmacy, stored in the unit, and changed at 1200 hours, multiple infusion bags would have to be contaminated if there was insulin poisoning. The blood sugar rose after 1900 hours, not because the infusion bag was changed, but because the dextrose was increased to 15%. Chase and Shannon (see Annex) reported that preterm infants have different insulin and c-peptide normative standards than adults. Exogenous insulin is unlikely to be the cause of hypoglycemia because the C-peptide was not low for preterm infants (20-45 percentile), potassium levels were normal (insulin decreases potassium), glucose levels should be lower if exogenous insulin was used, the Insulin / C-Peptide (I/C) ratio was within the expected range for preterm infants, insulin autoimmune antibodies (IAA) which are common in preterm infants bind to insulin and increase measured insulin levels, and the immunoassay test is unreliable because interference factors like sepsis and antibiotics can give false positive insulin readings.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Baby 6 had prolonged hypoglycemia because of sepsis, prematurity, borderline intrauterine growth

restriction, lack of intravenous glucose when the long line infiltrated for a prolonged period of

several hours, and poor medical management of hypoglycemia.

2. Baby 6’s insulin level and I/C ratio do not prove that exogenous insulin was used, and are within the

norm for preterm infants. Preterm infants and especially those with illness and drug treatments like

antibiotics have different normative standards compared to healthy adults and older children.

Prosecution opening statement

Background

The prosecution say Child F was marginally the younger of the twins, and he required some resuscitation at birth and later intubated, ventilated and given a medicine to help his lungs. He was recorded as having 'high blood sugar' so was prescribed 'a tiny dose of insulin'. He had his breathing tube removed and was given some breathing support.Child F had small amounts of breast milk and given fluid nutrients via a long line.

If it is known in advance that a baby cannot have milk and needs to be fed fluids then the TPN bag is prepared by the Aseptic Pharmacy Unit (APU) at the CoCH on receipt of a prescription.

The pharmacy bag is delivered back to the ward and is bespoke, prepared for an individual patient.

"If, for whatever reason, there is no need for a TPN bag, there are a couple of stock bags...kept in reserve."

"As a matter of practice", insulin is "never" added to a TPN bag.

Insulin is "given via its own infusion, usually in a syringe which delivers an automatic dose over a period of time".

The prosecution adds insulin is not added to a TPN bag as it would "stick to the plastic - or bind" to the bag, making it difficult to accurately give a reliable dose.

Incident

Early on August 4, Child E had died. Later that day, the pharmacy received a prescription for a TPN bag for Child F, the twin brother.A confirmation document was printed, at 12.32pm, for Child F. The pharmacist produced a handwritten correction to say it was to be used within 48 hours of 11.30pm that day.

The TPN bag was delivered up to the ward at 4pm that day.

On that nght shift, the designated nurse for Child F, in room 2, was not Letby.

Letby had a single baby to look after that night, also in room 2.

There were seven babies in the unit that night, with five nurses working.

Letby and the designated nurse signed the prescription chart to record the TPN bag was started and administered via a long line at 12.25am.

A TPN chart is a written record for putting up the bags, and was used for Child F. It includes 'lipids' - nutrients for babies not being given milk.

Letby signed for the TPN bag to be used for 48 hours.

There are two further prescriptions for TPN bags, to run for 48 hours.

Following the conclusion of a Letby night-shift, after the administration of a TPN bag Letby had co-signed for, a doctor instructed the nursing staff to stop the TPN via the longline and provide dextrose (sugar to counteract the fall in blood sugar), and move the TPN to a peripheral line while a new long line was put in.

All fluids were interrupted at 11am while a new long line was put in.

Child F's blood glucose increased, before falling back. A new bespoke TPN was made for Child F, delivered at 4pm.

The prosecution say this could not have been the same one fitted to Child F at noon that day which would have been either a bespoke bag which Lucy Letby co-signed for, or a stock bag from the fridge.

Mr Johnson said Child F's low blood sugar continued in the absence of Lucy Letby.

Child F's blood sample at 5.56pm had a glucose level was very low, and after he was taken off the TPN and replaced with dextrose, his blood glucose levels returned to normal by 7.30pm. He had no further episodes of hypoglycaemia.

"These episodes were sufficiently concerning" that medical staff checked Child F's blood plasma level. The 5.56pm sample recorded a "very high insulin measurement of 4,657".

Child F's hormone level of C-peptide was very low - less than 169.

The combination of the two levels, the prosecution say, means someone must have "been given or taken synthetic insulin" - "the only conclusion".

"That, we say, means that somebody gave Child F synthetic insulin - somebody poisoned him."

"All experienced medical and nursing members of staff would know the dangers of introducing insulin into any individual whose glucose values were within the normal range and would know that extreme hypoglycaemia, over a prolonged period of time, carries life threatening risks.

"No other baby on the neonatal unit was prescribed insulin at the time."

Mr Johnson: "To give Child F insulin someone would've had to access the locked fridge, use a needle and syringe to remove some insulin, or, if they didn't do it that way, go to the cotside and inject the insulin directly into the infant through the intravenous system, intramuscular injection, or - and this is what we say happened - via the TPN bag."

Medical experts

Medical experts Dr Dewi Evans and Dr Sandie Bohin said the hormone levels were consistent with insulin being put into the TPN bag prior to Child F's hypoglycaemic episode."You know who was in the room, and you know who hung up the bag," Mr Johnson told the jury.

Professor Peter Hindmarsh said the insulin "had to have gone in through the TPN bag" as the the hypoglycaemia "persisted for such a long time" despite five injections of 10% dextrose.

Professor Hindmarsh said the following possibilities happened.

That the same bag was transferred over the line, that the replacement stock bag was contaminated, or that some part of the 'giving set' was contaminated by insulin fron the first TPN bag which had bound to the plastic, and therefore continued to flow through the hardware even after a non-contaminated bag was attached.

"There can be no doubt that somebody contaminated that original bag with insulin.

"Because of that...the problem continued through the day."

Police interviews

Letby was interviewed by police in July 2018 about that night shift.She remembered Child F, but had no recollection of the incident and "had not been involved in his care".

She was asked about the TPN bags chart. She said the TPN was kept in a locked fridge and the insulin was kept in that same fridge.

She confirmed her signature on the TPN form.

She had no recollection of having had involvement with administering the TPN bag contents to Child F, but confirmed giving Child F glucose injections and taken observations.

She also confirmed signing for a lipid syringe at 12.10am, the shift before. The prosecution say she should have had someone to co-sign for it.

"She accepted that the signature tended to suggest she had administered it."

"Interestingly, at the end of this part of the interview she asked whether the police had access to the TPN bag that she had connected," Mr Johnson added.

In a June 2019 police interview, Letby agreed with the idea that insulin would not be administered accidentally.

Social media & text messages

In November 2020, she was asked why she had searched for the parents of Child E and F. She said she thought it might be to see how Child F was doing.She was asked asked about texting Child F’s blood sugar levels to an off- duty colleague at 8am. She said she must have looked on his chart.

Mr Johnson: "The fact it was done through the TPN bag tells you it wasn't a mistake - whoever was doing it was to avoid detection.

"Only a few people had the opportunity.

"We suggest there is only one credible candidate for the poisoning. The one who was present for all the unexpected collapses and deaths at the neonatal unit."

Defence opening statement

For Child F and Child L, the children allegedly poisoned with insulin, the defence "cannot say what has happened"."It is difficult to say if you don't know," Mr Myers said.

"So much has been said about these. These are not simple allegations which can automatically lead to a conviction."

The defence say Child F's TPN bag was put up by Letby in August 2015 and hours later there were blood sugar problems. That bag was replaced, in the absence of Letby, but the problems continued.

The sample taken came from "the second bag", the defence say.

A professor had given "three possible explanations", none of which identified Letby as a culprit.

For Child L, there were issues with the documentation provided, so those are challenged, the defence say.

There is "nothing to say" Letby was directly involved in the acts.

Defence Closing Speech

Mr Myers refers to the case of Child F. He discusses the counts of insulin in general - for Child F and Child L. He says the prosecution referred to Letby's 'concessions' of the insulin results. He says the defence reject she has committed an offence for those two counts. He says the jury 'may well accept' the insulin results. He says it is insufficient to say Letby's concessions that the lab results are accurate when she cannot say otherwise. He says the defence can't test the results as they have long since been disposed of. He says the evidence at face value shows how the insulin results were obtained. He says it is not agreed evidence.

He says 'it seems', insulin continued throughout, and Letby 'cannot be held responsible for, realistically'. He says Letby was accused of adding insulin to bags already put up [for Child F], or 'spiking it three times' for Child L. He says these explanations are "contrived and artificial".

Mr Myers says a 'striking' matter that neither Child F or Child L "come close" to exhibiting serious symptoms as a result of high doses of insulin. Child F had a vomit. Child L "only ever seemed to be in good health", other than low blood sugar levels.

He says for Child F, if accurate, received exogenous insulin administered, according to the laboratory result. He says it was 12.25am when a TPN bag is put up for Child F by Letby and a colleague, and that was changed at noon by two other nurses as the cannula line had tissued. He says the lab sample came at a time when Letby was not on duty, and was after the second bag had been put up. Mr Myers says the readings of blood glucose found for Child F and Child L are not that different for their respective days, but the levels of insulin found in the lab sample differ [Child F had a reading of 4,659; Child L had a reading of 1,099]. He says Professor Peter Hindmarsh was asked to describe the signs of high insulin/low blood glucose. He said there was the potential for brain damage in low blood glucose levels. The other symptoms in serious cases include death of brain cells, seizures, coma, and even death. He says "fortunately", "neither of these babies" exhibited the serious symptoms. He says that is surprising if both babies had the high levels of insulin alleged.

Mr Myers says it is "a strange intent to kill" when the person with intent would know a remedy would be available - a solution of dextrose. He says Letby helped administer that dextrose. He says it is "interesting" the proseution did not ask doctors to rule them out of involvement with insulin. He adds he is not making an allegation.

He says there is "no evidence" Letby interfered with any TPN bag. He says the fridge is used by "all nurses" on the unit, and the "risk would be obvious" that someone could be caught interfering with a TPN bag. He says there are "lots of reasons" to show Letby would be noticed if she were to carry the act of administering insulin.

Mr Myers says the defence make the "obvious" explanation that there is nothing to say Letby exclusively was responsible for the insulin being in the bag. He says insulin continued to be given to Child F after Letby had left the unit, via a maintenance bag. He says it is "incredible" that Letby is held responsible for this.

Mr Myers says the evidence is the stock [replacement] bag must have been contaminated with insulin. He asks how can Letby can be responsible for that bag, as no-one could have foreseen it would have been needed? He says the first bag was replaced as the cannula line had tissued. He says it is like "Russian dolls of improbability". He says a TPN bag lasts 48 hours. He says there are a number of stock bags kept, not kept in any particular order. He says there is no evidence no other babies subsequently displayed symptoms of high insulin from the other bags. He says unless Letby had a "Nostradamus-like" ability to read the future, in the event of a targeted attack, a stock bag would not be contaminated with insulin on the off-chance it would be needed, and the bag was the one chosen 'at random' by a colleague.

Mr Myers says Letby believed she had a good relationship with Child E and Child F's mother. He says there is an entry in Letby's diary on Child E - the only entry for any child in the indictment in the 2015 diary. He says there is no entry for Child F. He says the photograph of the sympathy card for Child E's parents, taken by Letby at the hospital, has no relevance. Mr Myers says it was a photo taken while she was at work.

Agreed Facts

Recorded Events and Messages

29th July 2015

Child F was born on July 29, 2015, at the Countess of Chester

Hospital, and had required some resuscitation at birth and was later intubated, ventilated

and given medicine to help his lungs.

31st July 2015

On July 31, a high blood sugar reading was recorded

for him, and he was prescribed a tiny dose of insulin to correct it. At this time his

breathing tube was removed and he was given breathing support.

4th August 2015

In the early hours of August 4, Child E had died. Later that day, just

before 5pm, a nursing note records family communication in which Child F's parents wish to

transfer care to another hospital in the North West, but transport was unavailable due to an

emergency. The note adds 'sincere apologies given to parents'.

The court is now focusing on the night shift of August 4-5, in which the prosecution allege Child F was poisoned on this night. A staff shift rota shows Belinda Simcock was the shift leader, with one nurse being the designated nurse for Child F in nursery room 2, and Lucy Letby being a designated nurse for the other baby in room 2 that night.

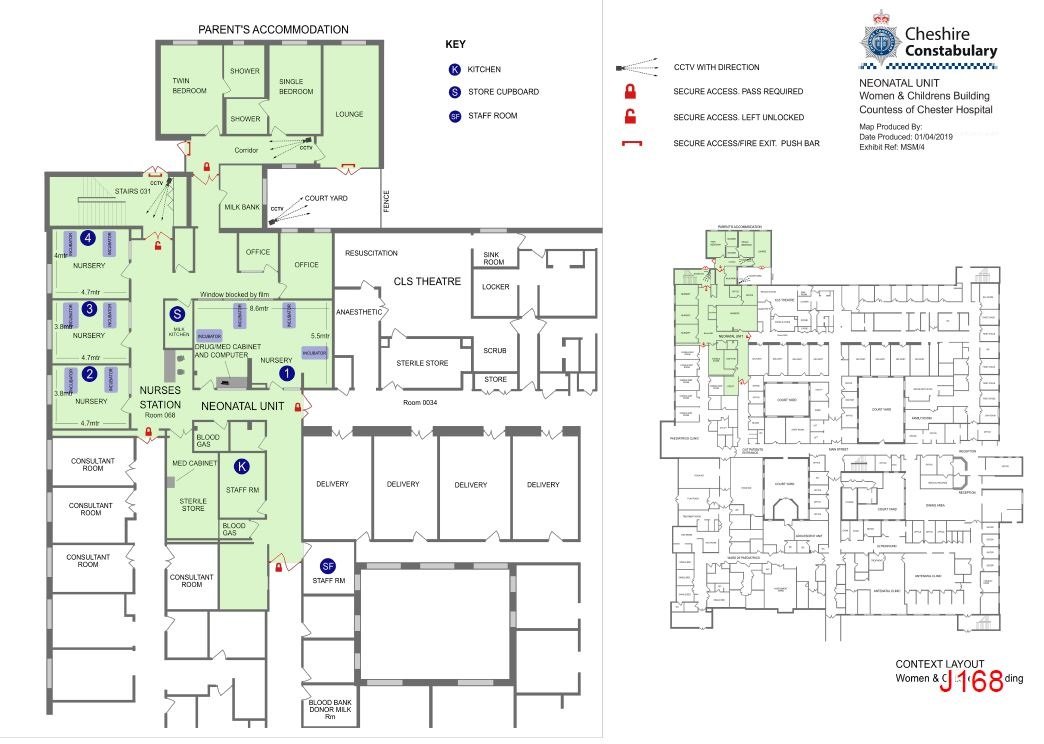

The court is shown a plan of the neonatal unit and the designated nurses for the babies on the unit that night.

That night, there was one baby being cared for in room 3, twins being cared for in room 4, and two other babies in the unit whose location cannot be established from the records, the court hears. There were a total of seven babies in the unit and five nurses on duty that night.

7.30pm: During the handover period at 7.30-8pm, a message from Letby's colleague Jennifer Jones-Key is sent to Letby's phone, saying: "Hey how's you? x"

8.01pm: Letby responds at 8.01pm: "Not so good. We lost Child E overnight.

x" [8.02pm]

Ms Jones-Key: "That's sad. We're on a terrible run at moment. We're you in 1? X"

[8.02pm]

Letby: "Yes. I had him & [another child]

Jones-Key: "That's not good. You need a break from it being on your shift."

Letby replied it was the "luck of the drawer [sic]".

Jones-Key: "You seem to be having some very bad luck though"

Letby: "Not a lot I can do really. He had massive haemorrhage which could have happened

to any baby x"

Jones-Key: "...Oh yeah I know that and it can happen to any baby. Very

scary and I have seen one"

Jones-Key: "Hope your [sic] be ok. Chin up"

Letby: "I'm ok. Went to [colleague] for a chat earlier on [and with] nice people

tonight."

Letby: "This was abdominal [bleed in Child E]. I've seen pulmonary before"

Jones-Key: "That's not good. It's horrible seeing it. "Hope your night goes ok"

9-10pm: The court is shown medication is being administered to Child F at this time, between 9-10pm.

11.32pm: A blood gas record result at 11.32pm shows a blood glucose level of 5.5.

A 48-hour bag prescription of nutrition is signed, solely, by Lucy Letby, recording it ending at 12.25am on August 5. Two records are shown for the next administration, the first being crossed out. The second nutrition bag has a higher level of Babiven, along with quantities of lipid and 10% dextrose that weren't on the first, crossed out, administration.

5th August 2015

12.25am: The Babiven is stated to start at 12.25am, and the lipid administration

is signed to begin at 3am. Letby is a co-signer for both the Babiven prescriptions, but not

the lipid administration.

12.25am: The 12.25am prescription for the TPN bag starts to be administered at 12.25am. Child F then suffered a deterioration, the court hears. A fluid chart shows Child F, for 1am in the 'NGT aspirate/vomit' column, four '+' signs.

1am: The nursing note, written retrospectively and timed for 1am, records: "large milky vomit. Heart rate increased to 200-210. [respiration rate] increased to 65-80. [Oxygen saturation levels] >96%. Became quieter than usual. Abdomen soft and not distended. Slightly jaundiced in appearance but no loss of colour. Dr Harkness R/V."

1.15am: An observation chart for Child F is timed at 1.15am. The heart rate is shown having increased, along with the respiration rate, at this time, into the 'yellow area', which the court has previously heard is something medical staff would note and raise concerns if necessary. Prosecutor Nicholas Johnson KC says the relevant nurse will be asked to give further details on this in due course. A blood gas reading for Child F at 1.54am has his blood glucose level as 0.8.

2.05am: Medication of 10% dextrose is administered intravenously at 2.05am, along with various other medications.

2.15-2.45am: Blood tests are ordered for Child F by doctors at 2.15am and 2.17am. They are collected between 2.33am and 2.45am.

2.55am: Child F's blood glucose level is recorded as 2.3 at 2.55am. This is still "below where it should safely have been", Mr Johnson tells the court.

3.10am: The lipid prescription is administered at 3.10am on August 5, with 0.9% saline administered at 3.35am.

3.50am: A 10% dextrose infusion is recorded at 3.50am.

4.02am: At 4.02am, Child F's blood glucose reading is 1.9.

4.25am: Further saline and 10% dextrose medications are administered at 4.25am.

5am: The blood glucose level is recorded as 2.9 at 5am.

7.30-8am: The shift handover is carried out at 7.30am, with day shift nurse Shelley Tomlins recording a blood glucose level for Child F as 1.7 for 8am. Prosecutor Mr Johnson says this is a "dangerously low level".

10am: Dr Ogden records a blood glucose level at 10am for Child F as '1.3'.

11.46am: The subsequent reading, recorded at 11.46am, is 1.4.

[Messaging with Nurse A]

Prior to this reading, Letby has been messaging the night-shift

designated nurse for Child F, saying: "Did you hear what Child F's sugar was at 8[am]?"

The nurse replies: "No?"

Letby: "1.8" The nurse replies: "[S***]!!!!", adding she felt "awful" for her care of

Child F that night.

Letby: "Something isn't right if he is dropping like that," adding that Child F's heel

has to be taken into consideration [as blood gas tests are taken via heel pricks, and cannot

be done too regularly].

The nurse responds: "Exactly, he had so much handling. No something

not right. Heart rate and sugars."

Letby: "Dr Gibbs came so hopefully they will get him sorted. "He is a worry [though]."

The nurse replies: "Hpe so. He is a worry."

Letby responds: "Hope you sleep well...let me

know how Child F is tonight please."

The nurse replies: "I will hun".

12pm: Child F's blood glucose level is recorded by a doctor as 2.4 at 12pm. Further medication administrations are made throughout the morning. A new long line is also inserted at this time.

Child F's blood glucose level is recorded as being:

2.4 at noon,

1.9 at

2pm

1.3 at 3.01pm.

4pm: More dextrose is administered. The blood glucose level is still "very low", the court hears, at 1.9 at 4pm.

At that time (4pm), Letby's phone receives an invitation from an estate agency firm confirming a viewing for a property in Chester, near the hospital. This home would be the address where Letby stayed until her 2018 arrest.

5.56pm: Child F's blood glucose level is recorded as being 1.3 at 5.56pm. A blood test is recorded for insulin to the Royal Liverpool Hospital at 5.56pm. The court hears those results did not come back for a week.

6pm: Child F's blood glucose level is recorded as 1.9 at 6pm.

Letby messages a colleague at 6pm to ask: "Hi! Are you going to salsa

tonite?"

The colleague responds: "Should do really as I haven't been for ages."

After

confirming she will, Letby responds with an 'ok' emoji.

Letby adds: "Need to try and find

some sort of nites energy", before clarifying "post nites" She adds, to conclude the

conversation: "Hasta luego".

7pm: A nursing note records there was a change from the TPN/lipid and 10% dextrose administration to 'just 15% dextrose with sodium chloride added'. The new fluids were commenced at 7pm.

7.30pm: The designated nurse [Nurse A] for the previous night shift returns to care for Child F on the night shift for August 5-6.

[Messaging with Nurse A]

She messages Letby to say: "He is a bit more

stable, heart rate 160-170." The long line had "tissued" and Child F's thigh was "swollen".

It was thought the tissued long line "may be" the cause of the hypoglycaemia.

The colleague added: "Changed long line but sugars still 1.9 all

afternoon. Seems like long line tissued was not cause of sugar problem, doing various tests

[to find the source of the problem].

Letby responds: "Oh dear, thanks for letting me know"

The nurse colleague replies: "He is def better though. Looks well. Handles fine."

Letby replies: "Good."

9.17pm: At 9.17pm, Child F's blood glucose level is recorded as being 4.1.

[Messaging with Nurse A]

11.58pm: Letby later adds, at 11.58pm: "Wonder if he has an endocrine problem then. Hope they

can get to bottom of it. "On way home from salsa feel better now I have been out."

The colleague replies: "Good, glad you feel better. Maybe re endocrine. Maybe just prematurity."

Letby replies: "How are parents?"

Colleague: "OK. Tired. They've just gone to bed."

Letby: "Glad they feel able to leave him."

Colleague: "Yes. they know we'll get them so good they trust us."

Letby: "Yes. "Hope you have a good night."

6th August 2015

1.30am-2am: Child F's blood glucose levels rose to 9.9 at 1.30am on August 6, a

repeat 9.9 reading being made at 2am.

7.58pm: Letby made the first of nine Facebook searches for the mum of Child E and F at 7.58pm on August 6.

Later Facebook searches and Messages

The searches were carried out between August 2015 and January 2016, and included a search on Christmas Day. One other search was carried out for the father of Child E and F on Facebook at 1.17am on October 5.

Letby sent a message to the designated nurse for Child F from those two night shifts, on August 9 at 10.17pm, saying: "I said goodbye to [Child E and F's parents] as Child F might go tomorrow. They both cried and hugged me saying they will never be able to thank me for the love and care I gave to Child E and for the precious memories I've given them. It's heartbreaking."

The nurse colleague replies: "It is heartbreaking but you've done your job to the highest standard with compassion and professionalism. When we can't save a baby we can try to make sure that the loss of their child is the one regret the parents have. It sounds like that's exactly what you have done. You should feel very proud of yourself esp[ecially] as you've done so well in such tough heartbreaking circumstances. Xxxx"

Letby: "I just feel sad that they are thanking me when they have lost him and for

something that any of us would have done. But it's really nice to know that I got it right

for them. That's all I want."

The colleague replies: "It has been tough. You've handled it

all really well."

"They know everything possible was done and that no-one gave up on Child E till it was

in his best interest. As a parent you want the best for your child and sometimes that isn't

what you'd choose. Doesn't mean that your [sic] not grateful to those that helped your child

and you tho xxx"

Letby: "Thank you xx"

On November 12, another colleague messages Lucy Letby at 8.32pm,

saying: "[Child E and Child F]'s parents brought a gorgeous huge hamper in today. Felt awful

as couldn't remember who they were till opened the card. Was very nice to them though n

Child F looks fab x"

Letby responds: "Oh gosh did they, awe wish I could have seen them.

That'll stay with me forever. Lovely family x"

Demo of Alaris Pump (for infusions)

A video is now shown to the court demonstrating how an Alaris pump, for infusions, is used at the Countess of Chester Hospital.Basic demo of Alaris Pump. Note: this is not the video used in court:

The pump has an air sensor at the machine part, and the video explains there is no real way air

could be added at any point in the infusion line.

The machine gives off an alarm if there is an 'occlusion' - or blockage - along the line.

The alarm can be silenced for two minutes by pressing a button. While that alarm is silenced, a red button would flash on the top of the machine.

An event log is displayed on the machine showing when the infusion starts/stops, if the rate is changed, and if it is primed.

The machine can store 100 events, and the log cannot be deleted by staff while it is on.

If the pump is switched off, and on restarting the option 'clear setup' is made, the event log is wiped.

The video explains that typically the events on there are not logged by Countess staff unless they are in relation to a serious health issue with the patient.

The video demonstrates what happens when an 'air bolus' - or air down the line - is in place when the machine is active.

The machine displays an 'occlusion' text warning and an alarm goes off.

A harsher sounding alarm then sounds, with 'air-in-line' displayed on the screen.

The machine can infuse at a maximum rate of 100ml/hr, the court hears.

Lucy Letby in the Witness Box

Direct Examination

Lucy Letby gave this evidence on 15th May 2023.The trial is now resuming. Lucy Letby will continue to give evidence on the case of Child F. She confirms that, in the 10 days since her last day of giving evidence, she has not spoken with her legal representatives.

Benjamin Myers KC tells the court Child F had low blood glucose levels throughout the day on August 5, 2015, and had a blood test which, when analysed, showed Child F had returned a very high insulin measurement of 4,657 (extremely high) and a very low C-peptide level of less than 169.

A chart is shown for Child F's blood glucose readings on August 5, which were 0.8 at 1.54am and remained low throughout the day, the highest being 2.9 at 5am but most readings were below 2.

A neonatal parenteral nutrition prescription chart is shown to the court, which shows Lucy Letby signed for a lipid infusion on August 1, the infusion starting at 12.20am on August 2. Lucy Letby tells the court it lasted just under 24 hours, being taken down at 12.10am on August 3.

There was already a TPN bag (a nutrition bag) in place on August 2, the court hears, as shown by the chart. It was a "continuing 48-hour bag". Midnight was "around the time" which fluids were changed. Letby has signed for a TPN bag at August 3, with a co-signer. The new bag is, on the chart, beginning at 12.10am. TPN bags last 48 hours, and lipid infusions last 24 hours.

A further sheet is shown for August 3-4, 2015. The 'continuing 48-hour bag' is signed for, but is not a new TPN bag, the court is told. That bag was discontinued at 12.25am on August 5. The chart shows a crossed-out prescription for August 5 for a TPN bag, where there is no lipid infusion. Letby tells the court Child F had been on milk. "Something changed" with those requirements and a second prescription was made for a TPN bag with lipids to be administered.

The new TPN bag was hung up at 12.25am on August 5. The bag was the same, the lipids requirements had changed, which meant a new prescription was written up. Two nurses were involved in hanging up the new TPN bag, the court hears. Letby is one of the two nurses who signed for it. Two nurses - neither of them Letby - are involved in the new lipid infusion.

Mr Myers asks if there is anything Letby did which accounted for Child

F's drop in blood sugar at that point.

Letby: "No."

A prescription chart is shown to the court, showing Child F received a 3ml, 10% dextrose bolus at 2.05am. Child F's blood sugar had risen by 2.55am, the court hears. Another 3ml, 10% dextrose bolus is given at 4.20am, and Child F's blood sugar level rose. Mr Myers says Letby's night shift would have ended as usual.

A chart is shown for a new TPN bag and lipid infusion for Child F at noon on August 5, which Letby confirms would have been after her shift ended. The TPN bag was hung up and a new long line was inserted as it had been "tissuing". Letby says if "tissuing" happens, it is "standard practice" to stop the administration, discard everything and start again with a new bag, as the TPN bag would have been sterile.

Mr Myers says "even after that", Child F's blood sugar levels remained low throughout the day. Mr Myers says this is not the same TPN bag Letby had hung up just after midnight. Letby confirms this.

Mr Myers asks why Letby searched for the mother of Child

E and F nine times on Facebook between August 2015 and January 2016, and the father on one

occasion.

Letby: "Searching people on Facebook is something I would do. Searching for [Child E and

F's mum] would be when she was on my mind. "...That is a normal pattern of behaviour for me."

Asked why Letby had taken a picture of a thank-you card written by the family of Child E and F, Letby replies: "It was something I wanted to remember - I quite often take photos of cards...I receive." Letby said she took a photo of the card at 3.40am one morning in the nursing station, while she was at work. She says there was "nothing unusual" about that.

Cross-Examination

Lucy Letby gave this evidence on 6th June 2023.Mr Johnson moves on to the case of Child F, the first of the two babies the prosecution say Letby poisoned with insulin. Child L is the other child allegedly poisoned by Letby. Letby denies she did this. Mr Johnson previously told the court the cases of Child F and Child L would be part of the cross-examination process together. Letby accepts the insulin readings which were shown for Child F - the insulin and insulin c-peptide numbers.

Letby says "there may have been some discrepancies" in the blood sugar levels for Child F. Mr Johnson says Prof Hindmarsh had told the court there would be discrepancies between a lab result and that taken from blood gas tests, 'of about 10-15%'.

Letby says she does not remember who put up the bag, as she did not recall, but as she had

no recollection of it, it would have been her nursing colleague [who cannot be named due

to reporting restrictions]. Letby says she co-signed the bag with [colleague].

LL: "To me, the other person who could have [put up the bag] would have been [my

nursing colleague]."

Letby says: "I can't answer that" to Mr Johnson's suggestion Child F had been targeted with insulin poisoning. Letby says she can accept insulin was given to Child F at some point. She says "if that's the evidence", then the insulin would have been administered via the TPN [nutrition] bag.

Letby accepts at the time of her arrest, she did not know or had heard about insulin c-peptide. Mr Johnson says the ratio between insulin and insulin c-peptide from the result had shown insulin had been administered. Letby says the TPN bag could have come from some other area than the neonatal unit.

The nursing staff rota for August 4-5 is shown to the court. Child F is in room 2, with Letby's colleague the designated nurse. Letby was in room 2 as the designated nurse for another baby.

Letby says she cannot say how the insulin got in Child F, so "I don't think I can answer" if staffing levels played a part in the poisoning of Child F.

Mr Johnson says Letby was "very keen" to ask police about the TPN bag said to

have had insulin in it.

LL: "Because I was being accused of placing insulin in the bag - I thought someone

would have checked the fluids."

LL: "I wanted them to check the bag, yes - I thought it would have been standard

practice [on the unit]."

Mr Johnson says Letby had not been questioned about Child F and

Child L in 2018, but was questioned about it in the following interviews. In it, Letby

asked police about the nutrition bags said to have had insulin in.

NJ: "You knew very well the bags wouldn't have been kept, didn't you?"

LL: "No." Letby had said to police if there had been concerns over the bags, they

would have been kept.

NJ: "You knew no concern had been expressed, didn't you?"

LL: "I didn't know no concern had been expressed at the time of this interview, no."

Police had asked why Letby had asked about the nutrition bags. Letby had said to police

there may "have been an issue with something else." Letby tells the court the issue may

have been insulin coming from outside the unit. She says at that point it was not known

where the insulin had come from, and it was not known if it was in the bags.

The trial is resuming after a short break.

Letby says she does not recall there were concerns for Child F's blood sugar level in her police interview in 2019. Mr Johnson says she was aware at the time. Text messages are shown to the court with Letby messaging a colleague about a low blood sugar reading.

NJ: "Had you seen something like this before? Babies having loads of dextrose and

still having low blood sugars?"

LL: "Yes."

NJ: "You were trying to [place it as natural causes]."

LL: "I don't think I was trying to provide an explanation."

Letby's message: "Wonder

if he has an endocrine problem then."

Mr Johnson: "Does that mean natural causes then?"

LL: "Yes."

Mr Johnson asks about the security of nutrition bags in the fridge, under

lock and key. He says they are not safe from someone with a key who can inject 'a tiny

amount of insulin' into the bag.

LL: "The bags are sealed and you would have to break the seal to do that."

Mr Johnson

asks if that would prevent someone from the previous shift from inserting insulin into the

bag.

LL: "I can't say that as I wouldn't put insulin into a TPN bag."

Mr Johnson says the

prescribed bag must have been 'tampered with' between 4pm on August 4 and 1am on August 5.

The replacement bag was a generic one. Mr Johnson describes how the insulin could be

administered after the bag has been delivered to the ward. One method is after the

cellophane wrap has been removed, to which he says that would mean there would be 'very

few candidates' who could have done that.

NJ: "Why would you not put insulin in the bags?"

LL: "Because that would go against [all standard practice]."

NJ: "It is highly dangerous.

LL: "Yes."

NJ: "Life-threatening to a child."

LL: "Yes."

NJ: "Something that would never cross the minds of medical staff?"

LL: "At the time? No."

Letby says she "cannot answer" if Child F was deliberately poisoned as she does not know how the insulin got there, who was there, or why.

Mr Johnson asks about the Facebook searches for Child E and Child F's mother carried out in the months after August 4, 2015. Letby says she got on well with the mother at the time, that she thought about Child E often, and wanted to see how Child F was doing.

Witness Evidence

Dr Gail Beech

See also: INQ0099074 - Thirlwall Inquiry Witness Statement of Dr Gail Beech, dated 24/05/2024.

Philip Astbury, prosecuting, is now calling Dr Gail Beech to give evidence.She was employed at the Countess of Chester Hospital as a paediatric registrar in summer 2015.

She was present at the birth of Child E and Child F, and looked after the former.

Her first involvement with Child F was during the day shift on August 4.

She says it would have been "usual practice" that she would have been told about the death of Child E as part of her hand-over for that day shift.

A 'ward round-up' is presented to the court, filled in, in preparation for the weekly consultant 'grand round' ward round-up on a Wednesday.

The list of problems, readings and observations for each child is noted, concluding with a management plan.

Dr Beech explains Child F was born premature, and the note recorded Child E had died aged six days.

Child F was on Optiflow, with 'suspected sepsis' noted, a raised urea and creatinine, 'jaundice' but not on phototherapy at this stage.

Child F was also 'establishing feeds' and awaiting genetics test for Down's, but Child F was not showing any clinical features, and 'hyperglycaemia - resolved'.

Mr Astbury says the genetic test results were received on August 7. Dr Beech said they confirmed there wasn't a presence of Down's.

Dr Beech confirms she was satisfied the hyperglycaemia [high blood sugar] level had been resolved.

Dr Beech said a standard list of medication was prescribed.

The Optiflow reading was not supplemented with oxygen - Child F had been 'in air since 3.30am'.

Oxygen saturation levels were 92-97%, which were 'satisfactory'.

Dr Beech says there 'weren't any concerns' on the cardiovascular system.

Child F weighed 1.296kg [2lb 13oz], from a birth weight of 1.434kg [3lb 2oz]. Dr Beech said this was not a concern as babies, particularly neonates, lose weight in the first days following birth.

Dr Beech confirms Child F was receiving nutrition via a TPN bag.

Child F was 'active, moving all 4 limbs'.

Child F was 'active and pink', with a 'clear' chest, no increased rate of breathing.

A note saying Child F required further tests on 'mouth and palate', and 'eyes', as part of a 'top to toe examination'.

The management plan says, for Child F, 'wean Optiflow flow when in air.'

'Complete 7 days of antibiotics'

"Continue increasing feeds as tolerated'.

'Chase genetics [for results]'.

'Complete examination and baby check later (parents arrived, upset about twin 1)'.

Dr Beech is now asked to look at a chart for a prescription for Babiven, which she has dated, but does not recall writing it.

She had signed for a rate of lipid, but that was zero as it wasn't required.

Babiven is a "standard bag" which would be given at a bespoke rate for Child F.

Dr Beech says the second prescription, with different Babiven levels and a new lipid level, was made as Child F had been made 'nil by mouth' and the increased levels were so Child F could acquire the same level of nutrients in his body.

Dr Beech is asked if there was anything notable from previous clinical records that she could recall in respect of Child F. She says there was not.

Her note at 5.40pm on August 5 documented 'asked to prescribe 150ml/kg/day 15% dextrose over 24hr at handover with 5ml/kg/day in it.

"Also to stop TPN, check urinary [sodium], cortisol and insulin."

Dr Beech says she cannot remember if Child F had been prescribed additional dextrose doses.

She says the 15% dextrose - a "high amount" - would normally be due to low blood sugar levels.

An intensive care chart is shown to the court, showing blood sugar levels which are "all low".

"2.9 [the 5am reading] isn't bad for a neonate - anything less than 2.6 is considered low"

Readings of 1.8 and 1.9 are shown for much of the day, up to 6pm.

10% dextrose solutions are administered at 3pm and 4pm.

A blood test is recorded at 5.56pm, sent to a laboratory, with 'relevant clinical details: preterm neonate, hypoglycaemia, on 10% dextrose'.

The blood glucose levels recorded are 1.3.

The 'lab sample' "tends to be more accurate" than one on a blood gas machine, Dr Beech tells the court.

The cortisol reading is 364, which is within the range of 155 to 607.

The insulin reading is 4,657.

The insulin c-pep reading is less than 169.

Dr Beech says the insulin reading is "very high" - while there is no 'normal upper limit', that reading could be considered high, the court hears.

The insulin c-pep reading is the lowest reading the machine can record.

The two readings [insulin and insulin c-pep] are "expected to be similar," Dr Beech tells the court.

A urine sample sent at 6.43pm had 'no unusual readings', but Dr Beech tells the court she cannot think, off the top of her head, how to interpret those results recorded.

A chart showing a 7pm prescription of 15% dextrose, with sodium chloride, is administered intraveneously. Dr Beech has signed that.

Cross Examination

Ben Myers KC, for Letby's defence, asks about the review she completed for Child F.

She clarifies she was waiting genetic test results for Child F for the presence of Down's Syndrome. Those results came back on August 7, with no evidence of Down's Syndrome.

Mr Myers asks if a further, microarray genetics test can be conducted to show for further potential genetic disorders. Dr Beech confirms that is the case.

Mr Myers says on August 4, the fluids were being administered via TPN, and milk coming in via the NGT [nasogastric tube], with no lipid required as Child F was getting milk in.

Mr Myers asks about the management plan - 'continue increasing feeds as tolerated'.

He then refers to the two August 4 prescriptions of fluids [the first being crossed out], and if Dr Beech had completed the figures. Dr Beech confirms that was the case, and that she signed for them.

At the first one, there is no component of lipid.

Dr Beech says she would have written these figures after the ward round, so the TPN could be made up.

Dr Beech says it would take some time from prescribing the TPN bag to it then being administered.

Mr Myers asks for clarity on how the second prescription comes to be made, with a different rate of administration of Babiven and a new lipid and new 10% dextrose doses.

Dr Beech confirms she did not prescribe these additional nutritions, as they are signed by a colleague.

The total nutrition administration is now 165ml and the rate is slightly increased from the first, crossed-out prescription of total 150ml fluid.

Dr Beech says the additional nutrition would come on separate infusions.

That concludes Dr Beech's evidence.

Nurse Shelley Tomlins

See also: INQ0017279 – Thirlwall Inquiry Witness Statement of Shelley Tomlins, dated 01/04/2024.

No live reporting - below taken from MailOnline article (23/11/22)Miss Tomlins told the court she recalled a new TPN intravenous feed bag being set up for Baby E after a longline tube needed to be replaced because it had 'tissued'.

This would have come from the padlocked fridge on the unit. Nurses had access to bespoke TPN bags for individual babies and stock bags for more general use or where there was no time to wait for a bespoke bag.

The bespoke bags lasted for either 24 hours or 48 hours, but seven years on from the incident she couldn't remember which.

Asked what type of feed bag would have been used on August 4, Miss Tomlins replied: 'It would depend on whether there were any more bags made up for him.

'If we had run out I assume we would have just attached to one of our stock bags and ordered more for him. It took a few hours for them to come from the pharmacy'.

She said the keys to both the fridge and the cupboards in Nursery 1 where drugs, insulin and intubation kits were kept together on the same bunch.

Asked by Simon Driver, prosecuting, who had possession of this, she replied: 'Usually the nurse in charge, but any one of us could ask for the bunch of keys and forget we had it in our pocket'.

She did not think a log was kept of who had the keys at any particular time.

Insulin was kept in the cupboards in Nursery 1, along with controlled drugs and the drugs needed for the intubation kits.

Mr Astbury put one final question to her, asking: 'Did you mat any point administer insulin to Baby F'.

She replied: 'No'.

Cross Examination

Miss Tomlins agreed with Ben Myers, KC, defending, that there was nothing unusual in a nurse signing on computer records for tasks that had actually been completed by a colleague.

'It wasn't strictly enforced,' she said. 'The 'user' simply means you're the one that is signed onto the system'.

Mr Myers: 'So you can't tell who has actually administered, can you?'

The nurse: 'No'.

Asked about the keys, she said they might happen to be with the last person who had gone to the fridge.

'Sometimes you had to ask around. You just used to say 'Who's got the keys?' You would not necessarily say where you were going with them, but it would be the fridge or the cupboard.

'They kept intubation kits in the fridge. These contained drugs that were needed so they were ready and you could get on with it'.

She said two nurses would check that a new TPN bag had been connected correctly, but it might be set up by a single nurse. If it was a prescribed bag, one nurse would sign the paperwork.

Nurse Sophie Ellis

See also:

INQ0017829 – Thirlwall Inquiry Witness Statement of Sophie Ellis, dated 11/04/2024

Mr Astbury repeated the question [“Did you at any point in time administer insulin to (Child F)?”] to Ms Ellis, giving evidence from behind a screen, who worked with Letby on the night shift of August 4.

Ms Ellis replied: “Absolutely not.”

Nurse Belinda Williamson

No live reporting - below taken from Chester Standard daily round up article (23/11/22)Finally Mr Astbury asked Ms Williamson, the shift leader on the night of August 4: “Did you during the course of the shift, at any stage, administer (Child F) any insulin?”

“No,” said Ms Williamson.

Doctor C (Thirlwall: Doctor ZA)

See also:

INQ0108001 - Letter from Doctor ZA to parents of Child E & Child F, dated 11/10/2023

Dr ZA's oral testimony at the Thirlwall Inquiry

She says she didn't have any direct treating care role for Child F.

The court is shown clinical notes on August 13 from a junior doctor colleague, in which she received genetic test results from Liverpool Women's Hospital.

The test had been conducted to check for signs of Down's Syndrome.

The doctor says Child F did not show any clinical signs of Down's at birth, and the test result showed no signs that was the case either.

The 'hypo screen results' were from a series of blood tests done when a baby has a "persistent" low blood sugar score. Some tests are conducted in the Countess of Chester hospital, some are taken to a laboratory in Liverpool, the court hears.

The doctor says the cortisol reading was 'normal', the insulin at a reading of 4,657 was "too high for a baby who has a low blood sugar".

The doctor says it would be expected, with a baby in low blood sugar, for insulin to stop being produced, so that would also be low.

The insulin c-peptide reading of 'less than 169' does not correlate with the insulin reading. The insulin and insulin-cpep readings would be 'proportionate' with each other.

The doctor says it was likely insulin was given as a drug or medicine, rather than being produced by Child F, to account for this insulin reading.

"This is something we found very confusing at the time," the doctor says, and said there weren't any other babies in the unit being prescribed insulin at that time, which would rule out "accidental administration".

The doctor says there are "some medical conditions" where a low blood sugar reading would also see a high insulin reading, but the low insulin c-peptide reading meant those conditions would be ruled out.

The insulin reading was "physiologically inappropriate", the court hears.

The doctor said those readings would be repeated, but as Child F's blood sugar levels had returned to normal by the time the test results came back several days later, there would be "no way" to repeat the test and expect similar results.

The doctor tells the court that Child F had received 'rapid acting insulin' on July 31, but the effect of that insulin would have "long gone" by the time the hypoglycaemia episode was recorded on August 5.

The clinical note added 'as now well and sugars stable, for no further [investigations].

"If hypoglycaemia again at any point for repeat screen."

The doctor says if Child F had any further episodes of low blood sugar, then the blood test would be carried out again.

The prosecution ask if anything was done with this data.

The doctor says it was looked to see if anyone else at the time was prescribed insulin in the whole neonatal unit, for a possible 'accidental administration', but there were no other babies at that time. No further action was taken.

Cross Examination

Ben Myers KC, for Letby's defence, asks to clarify that Child F's blood sugar had stabilised at that time. The doctor agrees.

The doctor clarifies, on a question from the judge Mr Justice James Goss, that the scope of the 'insulin prescription' checks were made for August 4 and August 5.

Dr John Gibbs

See also:

Neonatal Review conducted by Dr John Gibbs and Ann Martyn, dated 24/02/2017.

Dr John Gibbs' oral testimony at the Thirlwall Inquiry

He was the 'consultant of the week' the week when Child E and Child F were born, and the clincial responsibility meant he would go around the neonatal unit for a full examination, in addition to going around the unit every other day for observations, but not a full examination.

He said that was 'standard practice' for consultants in hospitals across the nation, as had been the case for many years.

He adds the number of neonatal unit deaths up to 2015 were within the normal range or lower than the average, up to 2015-2016.

He said the practice has since changed in 2016, in many hospitals, for there to be a 'consultant of the week' in the neonatal unit, and a separate 'consultant of the week' in the paediatric ward.

He said, for the Countess of Chester Hospital, it had followed the higher than expected mortality rate in the neonatal unit in 2015-16.

Dr Gibbs says the blood glucose levels for Child F, as noted by a colleague, soon after birth were 'satisfactory' at 2.7, as it should ideally be 'above 2.6'.

He said the following reading was '1.9', and that can be a 'natural consequence of the separation of baby from mother', so was not unusual in itself, and was more commonly seen in premature babies, the court is told.

Child F was "struggling with his breathing", so was started with an infusion with glucose.

The blood gas readings for Child F are shown for July 30-31, Child F having been born on July 29.

The glucose reading at 9.57pm for July 30 is '15.1' - an 'abnormally high' amount.

Dr Gibbs says the reading shouldn't go above 7.

He says that could be an indication for infection, and Child F was on antibiotics.

A single high blood sugar level reading would be monitored, and repeat high readings would lead to action taken, Dr Gibbs tells the court.

Because the blood sugar level reading on July 31 at 12.22am was 13.9, Child F was administered with insulin, "in a very small dose, carefully controlled", Dr Gibbs says.

Dr Gibbs says the administration of insulin at 3.40am meant the junior doctors had waited until a couple of high blood glucose readings had been recorded.

At 4.41am, the blood glucose level was 8.7, and Dr Gibbs says that meant Child F was "responding well" to the insulin infusion.

Dr Gibbs says the insulin infusion progress is "fairly predictable" and "you would expect" the blood sugar levels to decrease gradually.

He said: "It remained lower," so the insulin infusion was stopped at 6.20am.

Dr Gibbs' notes from August 2 are shown to the court, for his examination of Child F, a 'routine ward round'.

Dr Gibbs said he had seen Child F's twin brother, Child E, just before.

Child F was recovering from 'respiratory distress syndrome', was being treated for suspected sepsis, and had lost weight from birth, which was normal in newborn babies, the court hears.

The blood sugar levels were still 'moderately high', between 5-10.

He had 'some jaundice, which is common in premature babies', and a note for a heart murmur is made, but Dr Gibbs said he had not heard that upon examination of Child F.

Child F was on 'standardised' TPN fluid nutrition administration, plus nasal gastric feeds with expressed breast milk.

Dr Gibbs said 'standard' TPN bags would continue to be administered with newborn babies, with any tailored additives for babies, despending on their requirements, administered via a separate infusion method.

Child F had 'intermittent desaturations', which were not a cause for concern, the court hears.

Dr Gibbs said he couldn't hear a heart murmur, but the CPAP machine was on, so that may explain why he could not have heard any heart murmur - "or there may have been no heart murmur there".

Nurses had tried Child F off CPAP [breathing support] earlier that morning, which had led to oxygen desaturations, so he was put back on CPAP.

Dr Gibbs said Child F was likely recovering from respiratory distress syndrome.

The plan was to increase Child F's naso-gastric milk 'as tolerated'.

Dr Gibbs says the milk feeds were subsequently increased in the following days.

At August 5, at 1.30am, Dr Gibbs was on call when Dr Harkness reviewed Child F, following concerns over vomit and heart rate. Dr Gibbs was telephoned at 3.30am.

Dr Gibbs was told about the 'multiple small milky vomits and 9ml milky aspirate', and a heart rate above 200bpm, which he says was "high even for a premature baby".

Dr Gibbs said otherwise, Child F presented as a healthy baby.

The "sudden" increase of heart rate to over 200bpm was "very unusual".

Dr Harkness had 'assumed' the change in observations was down to an infection, and Dr Gibbs agreed, but Dr Gibbs said it was "a very rapid change, even for infection", and there would normally be signs of Child F deteriorating beforehand.

The plan was to rescreen for infection and start a new line for different, second-stage antibiotics.

The August 5 intensive care chart for Child F is shown to the court.

Dr Gibbs said as the naso-gastric feed tube was stopped [nil by mouth], that meant the TPN bag had to be changed to account for the administration of new medication, via a long line.

The blood glucose reading for Child F is 0.8 - "abnormally low" at 1.54am.

The August 3-4 readings shown are between 3.8 and 5.4, which Dr Gibbs says were normal.

Dr Gibbs says 0.8 is a "worryingly low reading for a baby".

A bolus of glucose was administered, with Dr Harkness giving an additional administration of glucose and sodium chloride, to 'keep the blood sugar level up'.

The following blood glucose reading of 2.3 at 2.55am was "much improved" but still low, so the plan for that would have been to continue to monitor the readings "carefully", Dr Gibbs says.

The additional provision was administered at 4am.

A reading of 2.9 was subsequently recorded.

Dr Gibbs said Dr Harkness likely had concerns over the heart rate raising suddenly, wondering if Child F had an "inherent problem" with the heart rate - [Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)]. However, those readings would see a heart rate of over 300bpm, so was recorded as "unlikely" on Dr Harkness's clinical note.

The consultation on the phone concluded infection as a possible cause, but the readings were "unusual to have such a sudden change in his observations".

Dehydration was also a possible cause.

Fluids and saline were administered to treat the possible causes.

Dr Gibbs said that Child F had an "extremely high" level of insulin in his body later that day, as revealed by a subsequent test result.

He added: "It makes it likely that his symptoms were related to very low blood sugar, [and can only be explained] by him receiving a high dose of insulin."

He said this was something he had concluded in hindsight. He had not come to this conclusion at 3.30am [during the telephone consultation], as he would not have had any reason to believe insulin had been administered.

Dr Gibbs' notes from 8.30am on August 5 recorded a 'natual increase in heart rate' due to Child F's stress.

The blood glucose reading was '1.7' despite administrations of glucose.

He also had signs of decreased circulation - a sign that he was "stressed, dehydrated, or had an infection".

While the blood sugar levels had risen to the '2's during the night, the latest reading of 1.7 was unusual and "unexpected" as Child F had had glucose administered, but did not seem to be responding.

Dr Gibbs: "At the time we didn't know this was because he had a large dose of insulin inside him".

Query marks were put on the note for sepsis - but the blood gas reading showed no sign of this, and for gastro-intestinal disease NEC, which had 'no clinical signs', as Dr Gibbs notes.

A plan was to give a 'further glucose bolus'.

The 'query query' was to consult the new 'consultant of the week' for a possible abdominal x-ray to look for signs of NEC, but Dr Gibbs tells the court this was not likely.

At 11am, the TPN, which includes 10% dextrose, was 'off' as the line had "tissued", and it was restarted at noon. That TPN was stopped at 7pm, and replaced with a 15% dextrose infusion, Dr Gibbs tells the court.

Dr Gibbs says the blood sugar levels remained "low, sometimes worryingly low" throughout the day.

The reading was 1.9 for much of the afternoon, despite three 10% dextrose boluses being administered during the day.

He adds after 7pm, the blood sugar readings, "at last", go to a "normal reading" of 4.1 by 9pm.

Dr Gibbs says the dextrose administrations had some minor effect at times, other times no effect.

He tells the court the assumption was infection, but it was "unusual" to have the blood sugar level remain so low, even with administration of 10% dextrose boluses, and that was what led to the call for a blood test to be carried out at the laboratory in the Royal Liverpool Hospital.

The blood sugar reading at 5.56pm on August 5 was "abnormally low" at 1.3, and the test was sent out to another laboratory as testing for insulin levels was a relatively "unusual" test.

The test result is shown to the court.

Dr Gibbs explains the readings.

He says the cortisol reading is 'satisfactory', but the "more relevant" reading was insulin.

"There should be virtually no insulin detected in the body...rather than that, there is a very high reading of 4,657".

The insulin C-peptide reading should, for natural insulin, should be even higher [than 4,657] in this context,

Dr Gibbs explains, but it is "very low"

The ratio of C-peptide/insulin is marked as '0.0', when it should be '5.0-10.0'

Dr Gibbs says the insulin c-peptide reading should be at 20,000-40,000 to correlate with the insulin reading in this test.

The doctor says this insulin result showed Child F had been given a pharmaceutical form of insulin administered, and he "should have never received it".

Cross Examination

Ben Myers KC, for Letby's defence, explains on this count [for Child F], Dr Gibbs will not be asked any questions on his evidence.

He adds that Dr Gibbs will be cross-examined on a future occasion in the trial on evidence that has been raised.

Nurse - unnamed

The next witness to give evidence is a nurse who cannot be named due to reporting restrictions. She has previously given evidence in the trial, and is now giving evidence in the case of Child F.The nurse confirms she had some involvement in the care of Child F, but was not the designated nurse.

She confirms she administered an infusion of glucose to Child F on August 5 at 8.30am.

She says it would have been a bolus of glucose given as a "push" response to low blood sugar.

An Alaris syringe driver video is displayed to the court, showing how a syringe dose can be electronically administered via infusion, at various rates. These rates can be locked.

It is similar to the Alaris pump, and has alarms if the syringe is not loaded properly, if the infusion has been placed 'on hold' for a certain length of time, if the rate has been changed but has not been confirmed, if the infusion is complete, if there is a power failure or low on battery, if there is an error message.

The alarm colour would be amber on the machine, and can be paused for two minutes.

An event log would be available on the machine for 24 hours.

The nurse confirms it was a standard machine used at the Countess of Chester Hospital, and was standard practice.

The nurse said the event log wouldn't be looked at routinely by staff.

An 'occlusion' alarm would be a red alarm light, with an alarm sound.

The syringe would be primed beforehand with the fluid, attaching the syringe to a line, and would be 'flushed' so no air would be present.

The nurse says a different piece of equipment would be used for TPN bags, and this equipment would be used for the lipid [fats] element administered via syringe.

The nurse says this equipment would be used to administer smaller amounts of fluids, such as 10% dextrose, or a saline bolus, or antibiotics.

The video demonstrates an 'accelerated rate' of a drug could be administered via infusion via a 'purge' function on the machine, which would be used as a possible bolus administration.

The nurse says that 'purge' button would not be used at the Countess of Chester Hospital, and was not standard practice.

The video adds the 'purge' function would not add to the total millilitres of infusion administered on the machine's display - ie, any fluids administered during that 'purge' time would not be added to the total the machine had calculated so far.

The machine also does not have the ability to detect air, the video presented to the court concludes.

An IV administration chart for August 5 is shown to the court, with four 10% dextrose infusions focused on.

The nurse has co-signed for two of the four administrations, both boluses at 8.30am and 3.15pm. One more would have been through a bolus and another via an infusion at a certain rate, which would require mechanical assistance.

The nurse said she would have delivered the two boluses she signed for as a 'push' infusion (ie, push the fluid manually via syringe attached to a clean, 'flushed' infusion line), and the process would be 'straightforward'.

The nurse is shown a note from the 'grand round', which the court heard was carried out by the on-call consultant each Wednesday.

The note 'new long line' was made, and the nurse says that was because the existing long line had tissued.

The new long line was made at noon on August 5.

The nurse says her normal practice would have been for putting a new bag of fluids on the long line.

The Alaris pump video is shown once again to the court, for the nurse to provide potential further context on what is demonstrated in the video.

The Alaris pump would be used in connection with TPN bags.

The nurse says while there is an input port on the TPN bag, she would not input anything manually in conjunction with the machine.

The output port would be used for 'giving' the infusion to the patient.

The nurse confirms a 10% dextrose administration was given to Child F at 3.30pm via an infusion.

She tells the court the 10% dextrose infusion would have been administered, in addition to the existing dose from the new bag at noon, as the blood glucose level was still low for Child F.

The nurse says the 3.30pm dose would have been administered via a syringe.

Lipids would have been administered via a syringe driver.

The court is shown a 15% dextrose dose, plus sodium chloride, is administered for 7pm on August 5. The nurse has signed for that medication administration.

The nurse is also a co-signer for medication at 2am on Thursday, August 6.

The nurse explains the practice was someone from the day shift (in this case, herself) would co-sign for the drug during the day, then she would in practice text the person who was administering it to confirm it had been administered, and that the scheduled dose could be taken 'off the system' and wasn't at risk of being administered twice.

Cross Examination

Ben Myers KC, for Letby's defence, asks about the administration of the drugs, and how they are administered.

The nurse says the 10% dextrose would come in 500ml bags, and can be divided up on the unit for infusions, or come available via the pharmacy in 50ml pre-made doses.

The nurse says she does not have an independent recollection of the event.

She confirms if the long line is tissued, it cannot be used again.

Mr Myers says if the long line is changed, then everything else is changed to avoid infection, including the TPN bag. The nurse confirms that would be the case.

Mr Myers: "You wouldn't put up an old [TPN] bag, would you?"

The nurse: "I wouldn't, no. And we wouldn't have put it up as we would have documented that."

Mr Myers says as a general rule, TPN bags would run for 48 hours unless there was a problem, and there would be a stock of maintenance bags in the fridge.

Mr Myers says one of those would have been used in the course of this. The nurse agrees.

The nurse says such bags are checked every night and if any were being used or out of date, then the stock would be replenished.

Prosecution

Simon Driver, for the prosecution, asks about the stock bags in the refrigerator.

He says every night, a check would be undertaken to see if any had been used.

He asks how the checker would know if they had been used.

The nurse says if there weren't the stock five TPN bags in the fridge, new ones would be ordered.

The refrigerator would have 'start-up' TPN bags and 'maintenance' TPN bags of nutrition.

The nurse says there may be fewer 'target stock' of the 'start-up' TPN bags.

Each of the bags would have a dated 'shelf life' the court hears.

The nurse says the bags would not be ordered in any particular fashion in the fridge.

A video of glucose/dextrose administration is played to the court.

The procedure is described as a 'two-person procedure'.

A question from a juror asks if the syringe driver could administer an infusion if the line has not been primed (ie if the line still has air in it).

The nurse confirms that would be the case. The equipment could have a filter connected, but it was the practice that the line would be primed before use.

End of reporting

Dr Anna Milan

See also: Trial transcript of Dr Anna Milan and Professor Peter Hindmarsh regarding Baby F (25/11/2022)

The court is hearing from Anna Milan, a clinical biochemist, how insulin and insulin c-peptide tests were taken for analysis.Child F's blood sample, which was dated August 5, 2015, was taken at 5.56pm.

The court is shown a screenshot of Child F's blood sample results. Child F is referred to as 'twin 2' - Child E, the other twin boy, had died at the Countess of Chester Hospital on August 4.

Dr Milan says Child F's insulin c-peptide level reading of 'less than 169' means it was not accurately detectable by the system.

The insulin reading of '4,657' is recorded.

A call log information is made noting the logged telephone call made by the biochemist to the Countess of Chester Hospital, with a comment made - 'low C-Peptide to insulin'

The note adds '?Exogenous' - ie query whether it was insulin administered.

The note added 'Suggest send sample to Guildford for exogenous insulin.'

The court hears Guildford has a specialist, separate laboratory for such analysis in insulin, although the advice given to send the sample is not usually taken up by hospitals.

Dr Milan said that advice would be there as an option for the Countess of Chester Hospital to take up.

Dr Milan said she was 'very confident' in the accuracy of the blood test analysis produced for Child F's sample.

Cross Examination

Ben Myers, for Letby's defence, asks about the risk of the sample deteriorating if it is not frozen.

Dr Milan said the sample arrived frozen. If it wasn't frozen, it would be accepted in 12-24 hours.

She said the laboratory knew it arrived within 24 hours, and adds Chester has its own system in place to store the blood sample before transport.

Mr Myers said the Child F blood sample would have been stored for seven days [in Liverpool], then disposed of. Dr Milan agrees.

On a query from the judge, Mr Justice James Goss, Dr Milan explains how the blood sample is frozen and kept frozen for transport.

She said the sample would not have been taken out of the freezer in Chester until it was ready to be transported.

Dr David Harkness

INQ0102350 – Thirlwall Inquiry Witness Statement of Dr David Harkness, dated 20/06/2024

Dr David Harkness is being recalled to give evidence.He has previously given evidence in the trial, and was employed at the Countess of Chester Hospital in summer 2015 as a paediatric registrar.

He is being asked about the night shift of August 4-5, and confirms he was accompanied by Dr Christopher Wood.

Notes showed he saw Child F on three occasions during that night shift.

He is asked about the 1.30am observations for Child F on August 5, of milky vomit and high heart rate.

He confirms the observations were made by himself.

He noted a 'soft continuous murmur' which is 'very common in babies'.

The plan was to rescreen, and use a second line for antibiotics.

There were "concerns" for Child F's heart rate, and that Child E, the twin baby boy, had passed away the previous night.

Dr Harkness's notes are shown to the court from 2.30am.

He noted Child F had 'large milky aspirate' and was 'quieter than usual'.

He said, from the heart rate observations being 'higher than normal', he was troubled by the possibility of infection, stress and pain, but those heart rates would go to 180bpm, not 200-210bpm, and come back down after a few seconds/minutes, not remain constantly high.

A septic screen and a number of blood tests were called for.

The blood sugar level of 0.8 [underlined on the note] was "very low".

Child F was "handling well" and pink and well perfused, indicating good circulation, Dr Harkness says, with heart sounds 'normal', but with a very quiet murmur.

The two problems were hypoglycaemia and tachycardia.

Dr Harkness's plan was for a dextrose bolus, a saline bolus, antibtiotics, an ECG, and to consider medicine to slow the heart rate down - but that medicine had its risks and would only be used in the event of supraventricular tachycardia.

Dr Harkness's note at 3.30am for Child F showed a heart rate of 204.

A discussion with the on-call consultant Dr John Gibbs, in which it was decided it was unlikely Child F had supraventricular tachycardia as the heart rate would be closer to 300bpm.

Dr Gibbs suggested repeating the fluid bolus, continue to monitor Child F, and only to consider the heart-slowing medicine if the heart rate rose to near 300.

A blood gas reading suggested Child F was dehydrated at this time.

The plan was to continue to monitor Child F's sugar levels.

A 10% dextrose infusion is administered for Child F at 3.50am, plus a 10% dextrose bolus at 4.20am.

Dr Harkness said the administrations had "an effect", but the blood sugar levels "kept drifting up and down".

Cross Examination

Mr Myers, for Letby's defence, says there will be no questions asked for Dr Harkness at this time.

Nurse A (Thirlwall: Nurse T)

See also: Nurse T's oral testimony at the Thirlwall Inquiry

No live reporting. Taken from daily round up 28/11/22On Monday, November 28, the jury at Manchester Crown Court was shown a form signed by Letby and her colleague confirming the nutrient bag was changed at 12.25am on August 5.

The colleague, who cannot be named for legal reasons, said she had no recollection of the specific event and could not be sure whether it was Letby or her who put up the bag.

Philip Astbury, prosecuting, asked the nurse if she had put anything in the nutrient bag.

She replied: “Absolutely not.”

She also answered “no” when asked if she gave Child F any insulin at any stage during that shift, in any way.

The court was shown messages sent between the witness and Letby after their night shift, in which they agreed Child F was a “worry” and Letby said: “Something isn’t right if he’s dropping like that.”

The nurse said Child F’s observations had been “within normal limits” before midnight.

She said: “I was really happy with him.”

She told the court tests from the earlier part of her shift showed he had a “good blood sugar level” and no concerns were raised when she had a handover at the start of her night shift.